I remember the first time I saw a picture of myself. I was a child, and my parents, freshly returned from the pharmacy, were eager to share some photos with me. As I looked at the photos they reviewed my expression intently, waiting for a response they didn’t receive. They kept pointing at the pictures, reiterating how cute I was, didn’t I remember? “That’s you,” they kept telling me.

The pictures left me cold. They were flat renderings, somehow more lifeless than the stills of a paused animated film. But my memory of what I’d been doing when the pictures were taken was vivid and rich: full of my grandmother’s papery scent and the thinning timbre of her laugh, my mouth busy with a freshly-peeled green grape. Her softness had been kind and the fabric of her dress scratchy but not offensively stiff like the starched points of my parents’ collars.

So much had been lost in the photograph. So much went unseen. I was unimpressed with the film’s ability to capture my image – my meat had done the job far better and captured not just an image but a memory. So it went.

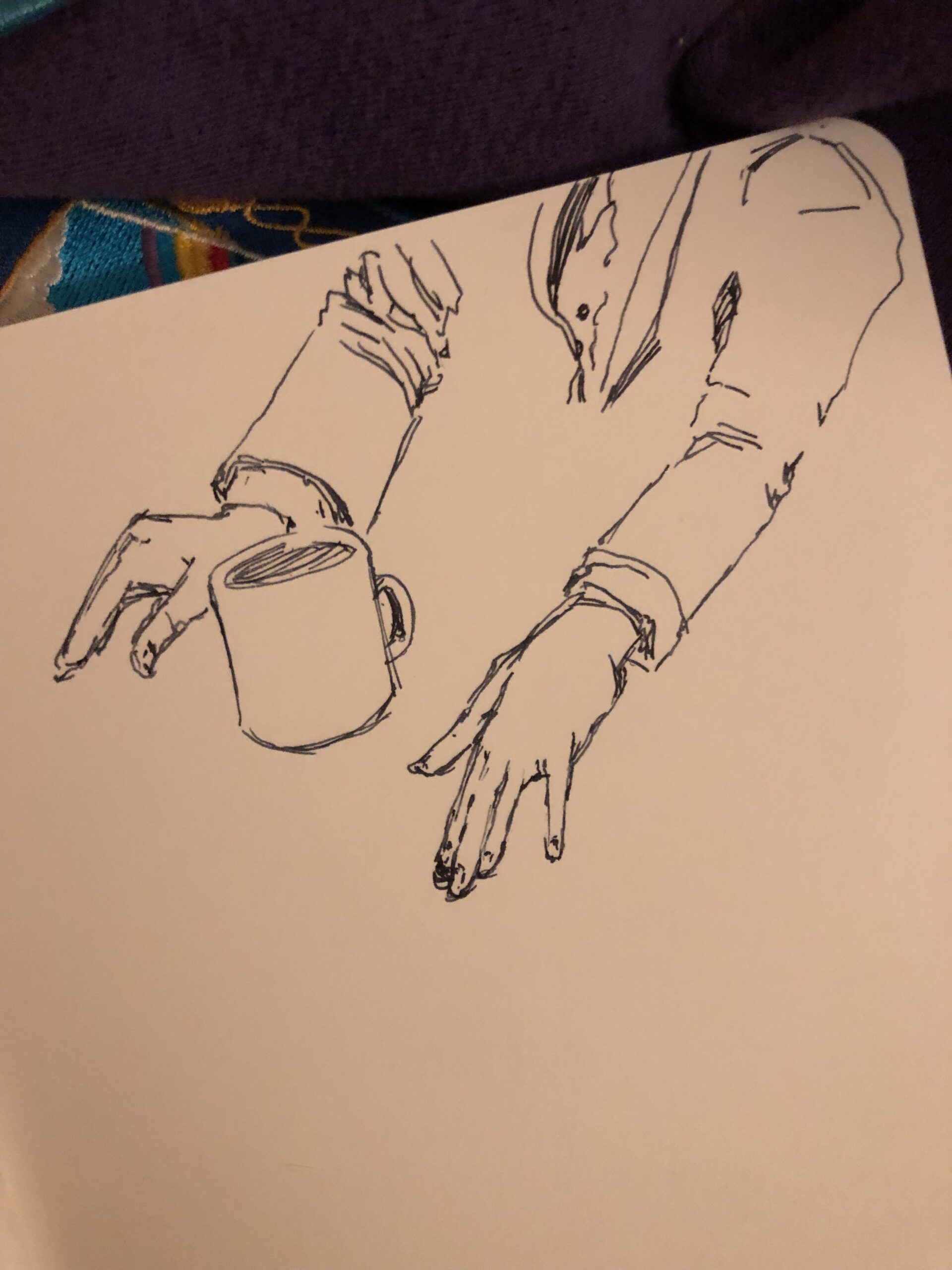

As I’ve grown up the ability to capture images on film, and later digitally, has both fascinated me and yet repeatedly fallen short. I’ve spent a lifetime as an artist struggling to depict what is really there in front of me: not merely the seen, but the fully perceived. How can we engage all the senses in two-dimensional art? How do you draw an intuition? An emotion? How do you capture all of that on film?

Social media doesn’t really give humans time to create in a thoughtful way. Instead, algorithms demand machine-like inflexibility. Creating consistent content and delivering it at consistent intervals has nothing to do with listening to the deep questions that move us forward as artists. Content creation is all advertising – it’s the selling of ourselves and our ideas to others. That’s capitalist nonsense, at times necessary, but it has nothing to do with the business of being human.

I believe that celebrating and honoring the memories we make in meaningful ways are how we live well. Taking pictures is secondary to that – they’re the souvenirs we take home along with any other ephemera we’ve picked up on the way. But social media reverses this, prioritizing the ephemera over the memory itself. You can get tons of likes and praise for a picture that gives you only the thinnest of pleasure to recall. Or you can experience deeply profound joy and receive no response at all.

I am aware that I am not made for social media. I post stuff to promote my horror writing and poetry, and I post things that I want to remember. My souvenirs are scattered like so much scrapbooking online, so when I open up my profiles I have something to smile about. But I spend most of my life either living it, or reflecting in my journals about my experiences. I know what I am: I’m human. I’m an artist. I’m an author. But I’m not a content creator, not really. I wasn’t built for that. I doubt you are, either.

Leave a Reply